Subtitle: The Art of Seeing Others Deeply and Being Deeply Seen

Author: David Brooks

Year: 2023

Publisher: Penguin Random

Pages: 304 (Hardcover)

Excerpt: The purpose of this book is to help us develop the skill of seeing and making others feel seen, heard, and understood.

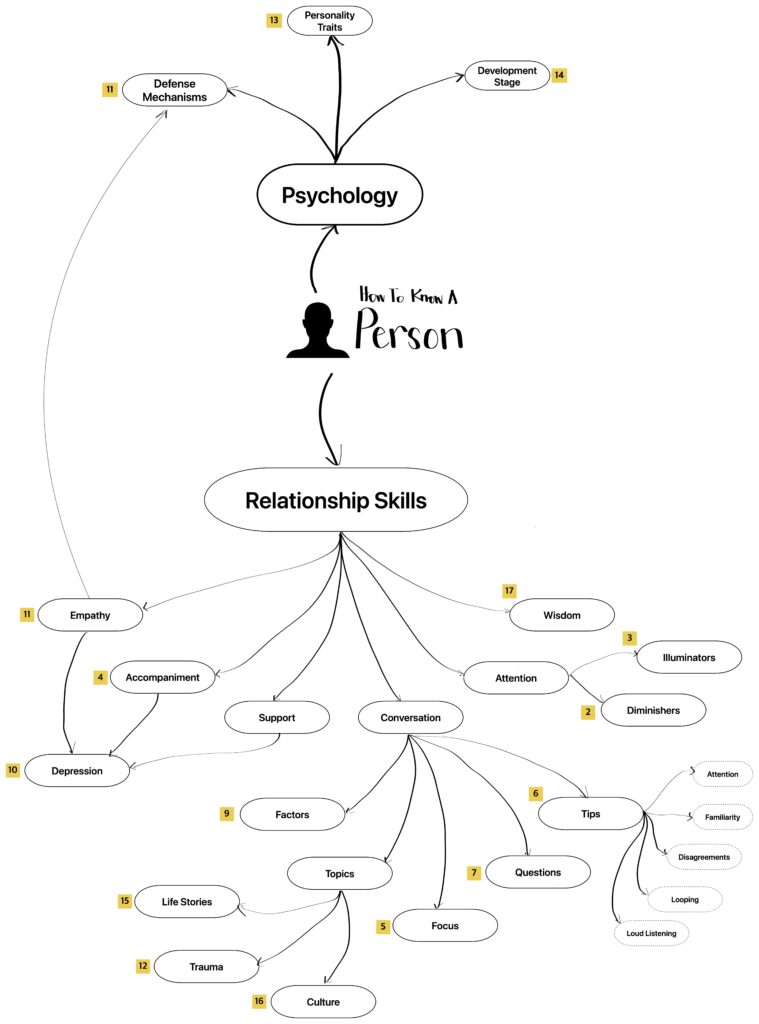

Part 1: I See You

The goal of Part 1 is to describe the skills needed to see and be seen by people on a personal level under normal or ‘healthy’ circumstances.

Chapter 1: The Power of Being Seen

Living disconnected from people is a withdrawal from life. We do not only disconnect from others, we also disconnect from ourselves.

In order to connect with people, we need to be open-hearted and have the skills to understand them. We need to be an illuminator instead of a diminisher.

Diminishers make people feel small and unseen. They see people as things to be used, not as persons to be befriended.

Illuminators make people feel seen. They are curious about people. They know what to look for and ask the right questions at the right time. They make people light up.

Chapter 2: How Not to See a Person

These are several of the ways a diminisher looks at a person

Egotism

Diminishers deems it beneath them to try to see others.

Anxiety

Diminishers focus more about how they look like to others.

Naive Realism

Diminishers assume how they see the world is the objective view.

Lesser-minds problem

Diminishers assume they have superior motivations than other people. We only have little access to what’s going on in other people’s minds because only a tiny portion of it is revealed by speaking, while we have all the access to what’s going on in ours. This makes diminishers think other people have lesser minds than them.

Objectivism

Diminishers think the best way to understand groups of people is by only seeing the data and statistics about them. However, we must focus on the thoughts and emotions of the individual, not just the data about groups.

Essentialism

Diminishers stereotype groups of people and draws conclusions from those stereotypes. They believe certain groups have an ‘essential’ nature to them. They believe people in the same groups are more alike than they actually are. They believe people in different groups are more different than they actually are.

Static mindset

Diminishers do not update their conception of you from when they first knew you. They don’t see that you have changed. They don’t see you for who you are right now.

Chapter 3: Illumination

Our gaze represents our attitude towards the world. When we look for beauty we will find wonder, when we look for threats we will find danger.

In order to find beauty in each person, we must assume that each person has something within themselves that has no definite size, shape, color, or volume, but gives them infinite value and dignity – their soul.

These are several of the ways an illuminator sees a person

Tenderness

Illuminators see the sameness and similarities between themselves and the other person.

Receptivity

Illuminators see the experience of the other person without thinking about their own insecurities, our opinion, and our viewpoint. They do not ask, “What would I do if I were in your shoes?” but instead, they wait for what the other person is offering.

Active Curiosity

Illuminators think what it would be like to live like the other person. They think about what it would be like to believe the things they do not believe.

Affection

Illuminators care for the other person. They do not merely try to know a person intellectually but also emotionally.

Holistic Attitude

Illuminators see the person as a whole and not from a one-sided point of view. They might see them as mean, but they also see them as angelic and compassionate. They understand that a person is a mass of contradictions.

Chapter 4: Accompaniment

When first getting to know someone, we don’t want to look into their souls right away. It’s best to look at something together and do something together. In this way, we get to be comfortable with the other person. We get to have subtle knowledge about each other before approaching other kinds of knowledge.

Accompaniment involves the following qualities:

Patience

Accompaniment involves being patient. We always need to be vulnerable in order to know a person. By having patience, we slowly build trust with the other person. When we try to know someone’s personal truths too aggressively, too impatiently, and too intensely, they will naturally defend or withdraw themselves from us. We have to stay in the dinner table longer. We have to sit with them in the chairs outside by the pool.

Playfulness

Accompaniment involves play. Play elicits all kinds of positive emotions. When we play, we get relaxed, be ourselves, and connect with others without even trying.

Power

Accompaniment involves giving up power over the other. It’s about letting them lead. It’s about letting them have their own journey while being alongside them.

Presence

Accompaniment involves showing up. It’s about showing up at weddings and funerals. We don’t have even have to say anything, we just have to be there and be aware of what they’re going through.

Chapter 5: What is a Person?

‘We do not see things as they are, we see things as we are.’

Anaïs Nin

We experience two layers of reality: the objective reality of what happens, and the subjective reality of how we interpret what happens.

In order to know a person, we must focus on their subjective reality.

Instead of asking, ‘What happened to this person? What are the items in their resume?’, ask questions like, ‘How does this person interpret what happened? How does this person see things? How does this person construct their reality?’

We must not pin them down and inspect them as if they were a lab sample, and reduce them to a type like MBTI, Enneagram, or Zodiac, or restrict them to a label.

In order to know a person, we must understand that their subjective reality changes over time.

A person’s model of the world normally changes gradually over time. However, when a person experiences a shocking event, their mental models can remake itself.

Ask questions like, ‘What are the experiences and beliefs that cause them to see things that way? What happened in their childhood that makes them see the world in this way? What was it in their home life that shapes their attitude about this?’

Chapter 6: Good Talks

How to become a better conversationalist

Treat attention as an on/off switch, not a dimmer

Either give someone all of your attention, or not give them any at all.

Favor familiarity

Look for something they are most attached to. People are more likely to talk about the movies they have already seen or the game they already watched. It’s more difficult to imagine and get excited about something unfamiliar.

Be a loud listener

Listen to them as if you are part of a congregation of a charismatic church by filling the air with grunts, ahas, amens, hallelujahs, and cries of “Preach!”. By responding to their stories loudly, we are inviting them to express more. When we listen to their stories passively, they are more likely to become inhibited.

Make them authors, not witnesses

Don’t just ask them what happened. Ask them how they’ve experienced what happened. Ask them what they were feeling when their boss told them they were laid off. Ask them what lessons they have learned from the experience.

Don’t fear the pause

Listen to learn rather than to respond. That means, do not think of a response while they are talking, but rather listen till the end. That also means, do not be afraid of taking a pause after they have spoken. Let what they’ve said sink in. Hold up your hand so they don’t keep on talking. And then take a couple of breaths.

Do the looping

Repeat what someone said to make sure you have accurately received what they’re trying to convey. Experts recommend this because people think they are more transparent and being clearer than they actually are. Respond to their story like, “What I hear is that you were really pissed at your mother.” They might respond like, “No, I wasn’t angry at my mother. I just felt diminished by her. There’s a difference.”

Don’t be a topper

When they say something that troubles them, don’t turn around and share your own troubles. When they share their experience, don’t respond by sharing a similar experience you have had. This turns the focus away from them and directs it to you. Sit with their experience first before sharing your own if you want to build a shared connection.

Find the agreement under the disagreement

When you’re disagreeing on something, find something common in your intentions. Say something like, “Even when we can’t agree on Dad’s medical care, I’ve never doubted your good intentions. I know we both want the best for him”.

Find the disagreement under the disagreement

When you’re disagreeing on something, find the deeper disagreement in your values or philosophy.

Chapter 7: The Right Questions

The following are examples of bad questions

Questions that evaluate

“Where did you go to college? What neighborhood do you live in? What do you do?”. These questions do not involve surrendering power but instead imply, “I am going to judge you”.

Questions that are closed

When you mention your mother and I ask, “Were you close?”. It limits the description of your relationship with your mother to a close/distant frame. Ask, “How is your mother?” instead. This gives the answerer the freedom to go as shallow or as deep as they want.

Questions that are vague

“How’s it going? What’s up?” These are impossible to answer and implies you’re only greeting them and you don’t really care about their answer.

The following are examples of good questions

Questions that prompts a story

“Tell me about the last time you went to the grocery stores late at night”, instead of “Why do you go to grocery stores late at night”. This allows the answerer to tell a story and redirect the conversation to things that really matter to them.

Questions about people’s hometown, cultural background, and family history

“Where did you grow up?”. This gets people to talk about their hometown.

“That’s a lovely name. How did your parents choose it?” This gets the answerer to talk about their cultural background and family history.

Questions that help find a commonality

“Do you ever have a glass of wine when you write?” If both of you is a writer. This is about finding commonality.

Questions that help look at life at a distance

- “I’m eighty. What should I do for the rest of my life?” This is a big yet very humble question. This allows people to talk about their values.

- “What would you do if you weren’t afraid?”

- “If we meet a year from now, what will be celebrating?”

- “Can you be yourself where you are and still fit in?”

- “What is something you need to refuse but keep postponing?”

- “What have you said yes to that you no longer believe in?”

Part 2: I See You in Your Struggles

The goal of part 2 is to help you understand and be present for people during harsh times like strife and conflicts.

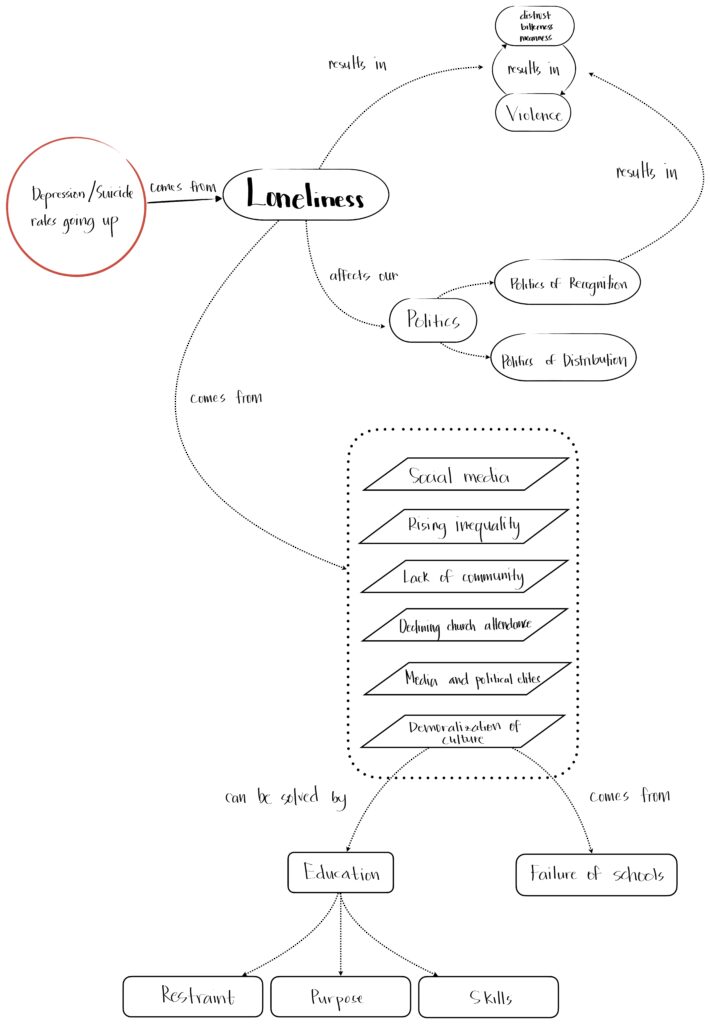

Chapter 8: The Epidemic of Blindness

In this chapter, Brooks points out a major problem in the world today, breaks down its root causes, and provides possible solutions.

Crisis

Depression rates in America are up. Suicide rates are up. Teens who experience feelings of sadness and hopelessness are up. Americans who don’t have romantic partners tripled. Americans who reported that they have no close friends quadrupled. People are spending time alone increased compared to spending time with friends.

The thing we need most is relationships. The thing we suck the most is relationships.

Root cause

Failure of schools to teach basic social and emotional skills. This leads to loneliness.

Consequences of loneliness

Loneliness causes people to become mean. It causes people to become more suspicious of others. It makes people take offense where none is intended. It makes people bitter. It makes people fear what they need the most – connection with others.

The source of evil is the tendency to destroy the humanity of others.

Causes of rising loneliness

Social media, widening inequality, declining community life participation, declining church attendance, rising populism and bigotry, demagoguery from media and political elites, and demoralization of culture.

Causes of demoralization of culture

Demoralization of culture comes from failure of schools to teach the skills and cultivate the inclination to treat each other with kindness, generosity, and respect. It also comes from schools abandoning to teach character education and focusing more on career and financial success.

Solutions for demoralization of culture

Demoralization of culture can be solved by helping people restrain their selfishness and care more about others, helping people find their purpose, so that their life has stability, direction, and meaning, and teaching people basic social and emotional skills so that they can be kind and considerate to the people around them.

Chapter 9: Hard Conversations

In order to know someone, we have to see them on the level of the individual: this person is a distinct and a never-to-be repeated being; on the level of social groups: this person is part of a group; and on the level of social location: this person sits on top of society or this person sits on the fringes of society. We have to see this person in all three levels at once when conversing with them.

How to have good conversations

Be genuinely curious

All conversations are affected by a person’s social groups and social location. We want to make sure that whatever social group we belong, they can be their full self with us. We can do this by having genuine curiosity about their life and work.

Focus on the actual conversation

All conversations have two levels: the official conversation and the actual conversation. The official conversation is the actual words we speak and the topics we talk about. The actual conversation is the emotions we give and take as we talk. Every comment we make is either making the other feel more safe or more threatened. Every comment we make shows how much we respect or disrespect them. Every comment we make reveals our intentions: ‘Here is why I am telling you this. Here is why this is important to me.’

Step within their frame

All conversations exists within a frame. The frame answers the questions: ‘What is the purpose here? What are our goals?’. The frame represents which point of view we are discussing from. When they are talking about times they felt betrayed or excluded, do not bring the frame back to yours. Instead, listen and stay within the other person’s standpoint. Understand how the world looks to them. And then, encourage them to go into more depth about what they have just said.

If we want to have a good conversation with someone, we have to step into their frame. It shows that at least we want to understand. It’s a powerful way to show respect. It allows both of us to contribute to a shared pool of knowledge.

How to have bad conversations

Not building a shared pool of knowledge

One person describes their own set of wrongs while the other does the same.

Labelling

One person discredits the other’s frame or point of view by labelling them: ‘You’re woke’, or ‘That’s a horrible way of thinking.’

How to recover from a bad conversation

Figure out what’s wrong

First, step back from the conflict and figure out what’s wrong. Ask the person, “How did we get to this tense place?”

Clarify your intentions and apologize

Second, clarify our own motives to the other person. First say what they are not, and then say what they are. We can say something like, “I wasn’t trying to lessen what you’re saying. I was trying to include your point of view with many other points of view in this topic. But I went too fast. I should have paused to try to hear what you are saying fully, so we could build from that reality. That was not respectful to you.”

Find the common intention

Third, identify the mutual purpose of your conversation that involve the both of you. Say something like, “You and I have very different ideas on the coding process. But we believe on the value our scripts provide to the company. We both want to make the process as efficient as possible so we can cover the most features in the least time.”

Create a deeper bond

Fourth, create a deeper bond from this conflict. We might say, “You and I have just expressed strong emotions, unfortunately against each other. At least we get to see where each other is coming from. Weirdly, we have a chance to understand each other better because of the mistakes we made and the emotions we’ve aroused.”

Chapter 10: How Do You Serve a Friend Who Is in Despair?

When we are trying to see into the world of a depressed person, we’d find out a nightmarish world which doesn’t follow any of our logic. We can only be humble in the fact that none of it makes sense.

These are what to do and what not to do when we have a depressed friend:

Do’s

- Acknowledge the reality of the situation.

- Hear, respect, and love them.

- Show them that you have not given up on them; that you have not walked away.

- Show them that you have some understanding of what they’re enduring.

- Create an atmosphere where they can share their experience.

- Offer them the comfort of being seen. It’s enough.

Dont’s

- Remind them of all the blessings they’ve enjoyed. Also called Positive reframing.

- Think that it’s impossible for this person to be depressed. Anyone can get depression.

- Cheer the person up.

- Ask them why.

- Try to make sense of depression.

Chapter 11: The Art of Empathy

If we want to know someone well, we have to know the ups and downs of their childhoods and the defense mechanisms or models they have used to survive that period and will probably carry with them for the rest of their lives.

Defense mechanisms

Avoidance

How to spot: People who are avoidant usually over-intellectualize life, feel comfortable when the conversation remain superficial, and retreat to work. They have low expectations in relationships. They tend to be overly positive to avoid displaying vulnerability. They want to be the strong ones others go to, but never the ones who turns to others.

How to understand: Avoidance is usually about fear. They often did not have close relationships as kids. They have been hurt by emotions and relationships so they minimize emotions and relationships.

What this person needs: This person in adulthood now wants to be attached.

Deprivation

How to spot: When treated badly, they tend to blame themselves. They carry the idea that they have some flaw deep within themselves, and if others knew it, they would run away.

How to understand: They were raised around self-centered people so their needs as a child were not met. This leads them to conclude that they are not worthy of love and attention.

What this person needs: This person in adulthood now wants to realize their full worth.

Over-reactivity

How to spot: They tend to see ambivalent situations as threatening ones. They see neutral faces as angry faces. They over-react to something and do not understand why they do so. They feel safe when they are on the attack against their enemies.

How to understand: They probably grew up in an abusive and threatening environment which makes them hyper-vigilant against any possible danger. They learned in childhood that life is combat.

What this person needs: This person now realizes that over-reacting causes ruin to themselves and their loved ones.

Passive aggression

How to spot: They may express agreement when deep inside they disagree. They let people know by withdrawal or expressions of self-pity.

How to understand: They most likely grew up in a home where anger is terrifying, negative emotions were not addressed, or where love was conditional. When they directly expressed their emotion, affection is taken away from them.

These defense mechanisms are not entirely bad. These have helped them survive against abuse and neglect.

Problems with defense mechanisms

- Over-identifying with them. When someone attacks their opinions, it feels like an attack on their identity. This causes them to lash out and see people as evil.

- You don’t control them; they control you. These defense mechanisms often need to find a target; which causes them to continually behave in ways where these defense mechanisms can be used.

- They get outdated. These defense mechanisms which were useful in childhood usually doesn’t work in the adult world. This causes them to make stupid decisions based on old models.

How can people overcome their defense mechanisms?

❌ Introspection. Introspection is not enough because our mind hides most of our thinking so we can get on with our life.

✅ Communication. Communication with other people allows us to have perspective outside of ourselves.

If communication is the key, it must be met with empathy for healing to take place.

Empathy consists of 3 skills

- Mirroring. This consists of identifying the emotion of the people in front of us and re-enacting their emotion in our body.

- Mentalizing. This involves knowing why this person experiences the emotions they currently have, and relying on our experience and memory to make predictions on what they’re going through. This is about projecting our memories onto them.

- Caring. This involves having the awareness that this person has a different consciousness than us and therefore might have a different way of dealing with the emotion than how we would personally deal with the same emotion.

How to increase empathy

- Proximity. It is difficult to hate people close up, so get in close contact with people physically. It helps if you sit in a circle so that everybody in the group feels equal to everybody else. It also helps if the group has the same focus and common goal so they can work on building something together.

- Drama. Play another character. Act as if you are another person.

- Literature. Read biographies or character-driven novels instead of plot-driven ones like thrillers and detective stories.

- Map. Use an emotion map and spot your mood on the map. Use Brackett’s RULER curriculum: Recognize, Understand, Label, Express, and Regulate.

- Suffering. Live and endure the up and downs of life. This allows us to have moments we can use to understand and connect with others.

Chapter 12: How Were You Shaped by Your Sufferings?

In order to know a person, we have to know who they were before and who they are after they suffered their losses.

There are two ways a person can respond to new information: assimilation and accommodation.

When we assimilate, we look at the new information in a way that already fits with our understanding of the world. When we accommodate, we change our understanding of the world to make sense of the new information.

Two ways we can respond to trauma is by closing ourselves to the world, or opening ourselves to the world – steeling or sharing. It is by sharing our griefs and secrets that we grow and we can do the process of accommodation.

How do we help ourselves and others engage in the process of accommodation? By using these excavation techniques.

Excavation techniques

Childhood fill-in-the-blanks

Ask your friends to fill in the blanks to these two statements:

- In our family, the one thing you must never do is … .

- In our family, the one thing you must do above all else is … .

This helps the person see what their family valued growing up.

This is Your Life

For couples: Write a summary of what happened throughout the year – the challenges your partner faced and how he/she overcame them – in first person from your partner’s point of view.

This helps you to see yourself from your loved one’s eyes. This helps people who have been hurt to overcome their self-contempt.

Filling in the calendar

Walk through the person’s life year by year. What happened in first grade? What happened in second grade?

Story sampling

Write about your emotional experiences for 20 minutes in a carefree way. Try to write from different perspectives.

As the narrative becomes more coherent, it becomes an act of self-creation. This would turn you from victim into writer.

Serious conversations with friends

Have a serious conversation with your friend about your lost loved one. Tell stories about them and what it would look like years ahead for you.

Part 3: I See You in Your Strengths

The goal of part 3 is to help us understand how to recognize the gifts other people bring to the world and how to celebrate their triumphs.

Chapter 13: Personality: What Energy Do You Bring into the Room?

A personality trait is a habitual way of seeing, interpreting, and reacting to a situation. A person’s personality traits can predict certain life outcomes as well as their IQ or socioeconomic status. So if you understand someone’s traits, you understand a lot about them.

Use The Big 5 (OCEAN) instead of Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) to understand personality traits because of its scientific validity and support.

Chapter 14: Life Tasks

In order to understand someone well, we have to understand the life task they’re currently on and how their mind has evolved to complete this task.

Common life tasks

The Imperial Task (Kegan)

A person in this stage focus on what they want and how to achieve what they want.

The Interpersonal Task (Kegan)

A person in this stage focuses more on relationships and how to achieve peace.

Career Consolidation (Kegan)

A person in this stage focuses on their career success and is willing to go against the crowd to do it.

The Generative Task (Kegan)

A person in this stage focuses on how they can be of service to the world.

Integrity vs Despair (Erikson)

A person in this stage focuses more on acceptance of the totality of their life and gaining wisdom.

Chapter 15: Life Stories

If we want to know a person, we have to know the stories they tell themselves and the stories they tell others about themselves. A person can only know what to do next if they know what story they are a part of.

In order to know a person’s stories, we must understand two types of thinking: Paradigmatic and Narrative. Paradigmatic thinking is logical and analytical. It’s about making an argument. It’s about understanding data. Narrative thinking is thinking in terms of stories. It’s about seeing how a person changes over time.

We can try to shift our conversations from paradigmatic to narrative mode, from comment-making to storytelling ones, by asking questions that prompts a story.

Shifting conversations to narrative mode

Focus on the journey

Instead of asking, “What do you think about X?”, ask “How did you come to believe X?”. Instead of asking, “What do you value the most?”, say “Tell me about the person that shaped your values the most.”.

Take people back in time

Ask questions like, “Where did you grow up?”. “What did you want to be when you were a kid?”. “When did you know that you wanted to spend your life this way?”.

Ask them about intentions and goals

Intentions implicitly tells where a person have been and where they hope to go. Ask questions like, “How do you hope to spend the years ahead?”

What to listen for when people tell their stories

Tone of voice

The tone of voice reflects the person’s basic view of the world. Is it sarcastic? sassy? ironic or earnest? cheerful or grave? Is it safe or threatening?

Point of view

How do they address themselves? Is it in first-person, second-person, or third-person? People who are able to distance themselves and address themselves in second-person or third-person are less anxious, gives better speeches, completes tasks more efficiently, and communicate more effectively. If you are able to distance yourself in this way, you should.

Character

The type of character they portray in their story reflects their identity. It reflects their ideal self and the role they hope to play in society. Are they the hero in their story? Are they the Healer? The Counselor? The Survivor? The Warrior? The Sage?

Plot

Quest – the hero goes on a journey to accomplish a goal and is transformed along the way.

Overcoming the monster – the hero defeats a threat.

Rags to riches – the hero starts from being unknown and poor to being famous and rich and prominent.

Narrator reliability

Are they self-flattering? Are they offering an accurate view of what happened? Are they telling you the positive as well as the negative side of themselves in the story?

Narrative flexibility

Are they able to update their views and opinions as they age? Are they able to include how their dreams changed from childhood to adulthood?

By inducing people to tell their stories, we are not only giving them the opportunity to be listened to, we are also giving them the opportunity to see themselves in a new way and to reconstruct their identities.

Chapter 16: How Do Your Ancestors Show Up in Your Life?

If we want to know a person well, we have to see them as culture-inheritors and culture creators.

Being a culture inheritor means being part of a long succession of humanity with a given set of history and gifts. Being a culture creator means taking some bits of culture here and rejecting some parts of culture there, incorporating these stories into our own.

Culture include stight or loose types, individualistic or collectivistic types, monogamous or non-monogamous types, settlement patterns, and religion.

That means during conversation, we need to ask them key questions: Where’s home? What’s the place you spiritually never leave? How do I see you embracing or rejecting your culture? How do I see you transmitting your culture? How do I see you caught between cultures?

Chapter 17: What is Wisdom?

Wisdom is knowing about people. Wisdom is the ability to see deeply into who people are and how they should move in the complex situations of life.

Wise people are more like coaches than philosopher-kings. They don’t tell you what to do but instead, they help you process your own thoughts and emotions. They have lived a full life and reflected on what they’ve been through.